Thunderstor Serial

Jun 09, 2015 This document provides facts about windstorms called derechos and shows examples of major derecho events that have occurred in North America.

The LS7002 is an Advanced Total Lightning sensor. It detects low frequency LF electromagnetic signals generated by lightning in order to provide extremely.

Thank you for signing up for special offers, product announcements and news. Sign up today for the latest news and product updates from Belkin.

The latest in high tech radio control hobby products. Find innovative RC aircrafts, vehicles, and accessories like the Phantom Quadcopter and GoPro Hero3.

Part

of the NOAA-NWS-NCEP Storm Prediction Center web site

Prepared by Robert H. Johns, Jeffry S. Evans, and Stephen F. Corfidi with the help of many

others

Last updated on March 1, 2012;

check What s New

link below to see what has been added or changed.

Photo of the gust front arcus cloud on

the leading edge of a derecho-producing storm system. The photo was taken on the evening of July 10, 2008 in

Hampshire, Illinois as the derecho neared the Chicago metropolitan area. The derecho had formed around

noon local time in southern Minnesota.

WHAT S

NEW

INTRODUCTION

Definition of

a derecho

A derecho pronounced similar to deh-REY-cho in English,

or pronounced phonetically as

is a widespread, long-lived wind storm that is associated with a band of rapidly

moving showers or thunderstorms. Although a derecho can produce destruction similar to that of tornadoes,

the damage typically is directed in one direction along a relatively straight swath. As a result,

the term straight-line wind damage sometimes is used to describe derecho damage.

By definition, if the wind damage swath extends more than 240 miles about 400 kilometers and includes

wind gusts of at least 58 mph 93 km/h or greater along most of its length, then the event may be classified

as a derecho.

Click

here to hear a pronounciation of the word derecho.

Because derecho is

a Spanish word see paragraph below, the plural term is derechos;

there is no letter e after the letter o.

Origin of the term derecho

The word derecho was coined by Dr. Gustavus Hinrichs, a

physics professor at the University of Iowa, in a paper published in the American

Meteorological Journal

in 1888. A defining excerpt from the paper can be seen

in this figure showing a derecho crossing Iowa on July 31, 1877.

Hinrichs chose this terminology for thunderstorm-induced straight-line winds as an analog to the

word tornado. Derecho is a Spanish word that can be defined as direct

or straight ahead. In contrast, the word tornado is thought by some, including

Hinrichs, to have been derived from the Spanish word tornar, which

means to turn.

A web page

about Gustavus Hinrichs has been created by National Weather Service Science and

Operations Officer Ray Wolf. The page provides information on Hinrichs background and

on his development of the term derecho in the late 1800s. Wolf s page also

briefly discusses how the term derecho came into more common use in the late 1900s.

DERECHO-PRODUCING STORMS

Derechos are associated

with bands of showers or thunderstorms collectively referred to as convection that

assume a curved or bowed shape. The bow-shaped storms are called bow

echoes. Bow echoes typically arise when a storm s rain-cooled outflow winds are strong,

and move preferentially in one direction.

A derecho may be associated with a single bow echo or with multiple

bows. Bow echoes themselves may consist of an individual storm, or may be comprised of

a series of adjacent storms i.e., a squall line or quasi-linear convective system that together take on

a larger scale bow shape. Bow echoes may dissipate and subsequently redevelop during the course of given

derecho. Derecho winds occasionally are enhanced when a rotating band of storms called

a bookend vortex develops on the poleward side of the bow echo storm system. Derecho winds

also may be augmented on a smaller scale by the presence of embedded supercells

in the derecho-producing convective system.

Derecho winds are the product of what meteorologists call downbursts. A downburst is a concentrated area of

strong wind produced by a convective downdraft. Downbursts have horizontal dimensions of about 4 to 6 miles

8 to 10 kilometers, and may last for several minutes. The convective downdrafts that comprise downbursts

form when air is cooled by the evaporation, melting, and/or sublimation of precipitation in thunderstorms

or other convective clouds. Because the chilled air is denser than its surroundings, it becomes negatively

buoyant and accelerates down toward the ground. Derechos occur when meteorological conditions support the

repeated production of downbursts within the same general area. The downburst clusters that arise in such

situations may attain overall lengths of up to 50 or 60 miles 80 to 100 kilometers, and persist for

several tens of minutes. Within individual downbursts there sometimes exist smaller pockets of intense winds

called microbursts. Microbursts occur on scales approximately 2 1/2 miles or 4 km that are very

hazardous to aircraft; several notable airline mishaps in recent decades resulted from unfortunate

encounters with microbursts. Still smaller areas of extreme wind within microbursts are called burst swaths.

Burst swaths range from about 50 to 150 yards 45 to 140 meters in length. The damage they produce may resemble

that caused by a tornado.

A typical derecho consists of numerous burst swaths, microbursts, downbursts, and downburst clusters. The

schematic below illustrates the spatial relationships between these features.

DERECHO DEVELOPMENT

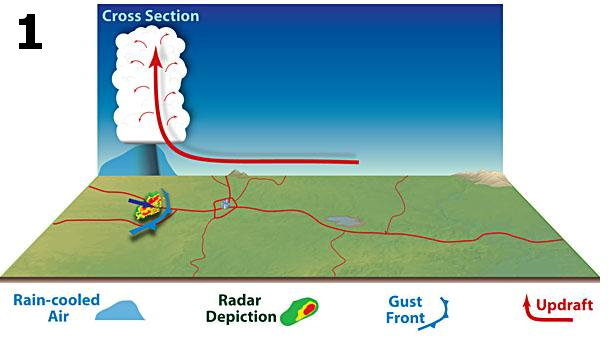

Derecho development necessarily is tied to the formation of bow echoes. A bow echo usually arises from

a cluster of thunderstorms, but also may evolve from a single strong storm. Bow echoes most frequently occur

when tropospheric winds are relatively strong and unidirectional i.e., they vary little in direction with

height. As the rain-cooled downdraft of a thunderstorm reaches the earth s surface, it spreads horizontally,

most rapidly in the direction of the mean tropospheric flow. As the cool, dense air spreads outward, it

forces the lighter, warm and moist air surrounding the storm up along the leading edge of the outflow, or

gust front see figure below, with mean flow assumed to be from left to right. The upward motion along the

gust front typically is greatest along that part of the front that is moving most rapidly, that is, in the

downwind direction to the right in the figure. Gust fronts often are marked by a band of ominous, low

clouds known as arcus. An example of an arcus cloud appears at the top of this page.

The development of a thunderstorm s downdraft ordinarily marks the dissipation stage of that particular storm.

But air forced up along a gust front can give birth to new thunderstorms. As new storms mature,

the rain they produce reinforces the existing pool of rain-cooled air produced by earlier storms, allowing

the gust front to maintain its strength. As this cold pool increases in size and elongates in the direction of

the mean wind, it induces an inflow of air known as the rear-inflow jet dashed brown arrow in figure below on

the trailing side of the thunderstorm complex. This causes the updraft to tilt toward the rear side of the storm

i.e., to the left in the figure. Tilting of the updraft allows the thunderstorm to further expand,

increasing the aerial coverage of the rain. This, in turn, adds to the pool of cold air accumulating beneath

the storm and strengthens the gust front, causing it to bow outward in the downwind direction. The resulting

acceleration in forward motion of the gust front subsequently forces more warm, moist air upward, creating

still more storms, and the process repeats.

The rain produced by the newer storms reinforces the cold pool and strengthens the inflow of air from the back

side of the developing storm complex, enabling the complex to attain a nearly steady-state condition. At this

point, the convective system typically exhibits a pronounced bow shape on radar see figure below, with an

area of moderate to occasionally heavy rain located near the center of the cold pool, well behind the arc of very

heavy rain immediately behind the gust front. As long as the thermodynamic and kinematic environment support the

continued development of new thunderstorms along the advancing gust front, the convective complex will persist,

along with the potential for downbursts and microbursts.

TYPES

OF DERECHOS

Two main types

of derechos may be distinguished. This classification largely is based on the overall organization and behavior of the

associated derecho-producing convective system and reflects, in part, the dominant physical processes responsible for the thunderstorms

that produce the damaging winds.

The type of derecho most often encountered during the spring and fall is called a

serial derecho. These are produced by

multiple bow echoes embedded in an extensive squall line typically many hundreds

of miles long that sweeps across a very large area, both wide and long. This type

of derecho typically is associated with a strong, migratory low pressure system.

An example of a serial derecho with a very extensive squall line and embedded smaller

scale bow echoes is the one that affected Florida, Cuba, and adjacent parts of the Gulf of

Mexico, the Caribbean Sea, and the Atlantic Ocean during the early stages of the Storm of the

Century on March

12-13, 1993.

The second type

of derecho is called a progressive

derecho. These are associated with a relatively short line of thunderstorms

typically from 40 miles to 250 miles in length that may at times take the

shape of a single bow echo, particularly in the early stages of development.

In some cases, the width of a progressive derecho and its associated bow echo

system remain relatively narrow even though they may travel for hundreds of

miles. An example of this type is the Boundary

Waters-Canadian Derecho that occurred on July 4-5, 1999. In other

cases, the progressive derecho and associated bow echo system begin

relatively small, with a narrow path, but over time grow to exceed 250 miles in width.

The line of thunderstorms of a progressive derecho often begins as a single bow echo that evolves into

a short squall line, typically with more than one embedded bowing segment. Such development occurred with

the I-94 Derecho over

the north central United States on July 19, 1983 see Fig. 2 in that event s discussion page. Progressive

derechos may travel for many hundreds of miles along

a path that is relatively narrow compared to those of serial derechos. Often they are associated with an

area of weak low pressure at the surface.

Occasionally, derechos having characteristics

of both serial and progressive events are observed. These events are known as a hybrid quot derechos.

For example, the Southern Great Lakes Derecho of May 30-31, 1998 was

attendant to a strong, migrating low pressure system. However, the derecho path and the associated

bow echo convective system had many characteristics of a progressive derecho.

In contrast to most derecho-producing thunderstorm systems which typically occur in association with very moist air,

bands of widespread wind-producing storms sometimes occur in environments of very limited moisture. These systems

are referred to as low dewpoint derechos.

Such derechos most often occur between late fall and early spring in association with strong low pressure

systems, and are a form of serial derecho.

The schematic below highlights the distinguishing features of serial and progressive derechos.

STRENGTH

AND VARIATION OF DERECHO WINDS

Strength

of derecho winds

By definition, winds

in a derecho must meet the National Weather Service criterion for severe wind

gusts greater than 57 mph at most points along the derecho path. But in stronger

derechos, winds may exceed 100 mph. For example, as a derecho roared through

northern Wisconsin on July 4, 1977,

winds of 115 mph were measured. More recently, the derecho that swept across

Wisconsin and Lower Michigan during the early morning of May

31, 1998 produced a measured wind gust of 128 mph in eastern Wisconsin, and

estimated gusts up to 130 mph in Lower Michigan.

Variation of wind speeds

in a derecho

The winds associated with derechos are not constant and may vary considerably

along the derecho path, sometimes being below severe limits 57 mph or less,

and sometimes being very strong from 75 mph to greater than 100 mph. This is because, as previously

noted, the swaths of stronger winds within the general path of a derecho are produced by

downbursts, and downbursts often occur in clusters, along with embedded microbursts

and burst swaths. Derechos might be said to be made up of families of downburst

clusters that extend, by definition, at least 240 miles about 400 km in length. The derecho of

July 4-5, 1980 is a good example of an event that exhibited wide

variation in observed wind speeds.

CASUALTY AND DAMAGE RISKS

FROM DERECHOS

Those most

at risk from derechos

Because derechos are most common in the warm season, those involved in outdoor

activities are most at risk. Campers or hikers in forested areas are

vulnerable to being injured or killed by falling trees. People in boats

risk injury or drowning from storm winds and high waves that can overturn boats.

Those in cars and

trucks also are vulnerable to being hit by falling trees and utility poles.

Further, high profile vehicles such as semi-trailer trucks, buses,

and sport utility vehicles may be blown over. At outside events such as

fairs and festivals, people may be killed or injured by collapsing tents

and flying debris.

Even those indoors

may be at risk for death or injury during derechos.

Mobile homes, in particular, may be overturned or destroyed, while barns and similar buildings

can collapse. People inside homes, businesses, and schools are sometimes victims of

falling trees and branches that crash through walls and roofs; they also may be injured by flying glass

from broken windows. Finally, structural damage to the building itself for example, removal of a roof

could pose danger to those inside.

Another reason that

those outdoors are especially vulnerable to derechos is the rapid movement of the parent convective system.

Typically, derecho-producing storm systems move at speeds of 50 mph or greater, and a few have been clocked at 70 mph.

For someone caught outside, such rapid movement means that darkening skies and

other visual cues that serve to alert one to the impending danger e.g., gust front clouds

--- see photo at top of page appear on very short notice. In summary, the advance notice given by

a derecho often is not sufficient for one to take protective action.

A camper s close brush with death in Maine

during the July 4-5, 1999 derecho is told here.

A boater s encounter with the May 17, 1986 derecho on Lake

Livingston, Texas is described

here. The dramatic account of a boat being overturned by

intense straight-line winds is given on the Northern Indiana National Weather Service s web page linked

here.

The causes of injury or death

for the 73 casualties of the July 4-5, 1980 derecho is given

here. This event

provides a good example of the various risks posed by derechos.

Special

hazards posed by strong derechos in urban areas

Whether in an urban

or rural area, those out-of-doors are at greatest risk of being killed or injured

in a derecho. But a hazard of particular significance in urban areas is the

vulnerability of electrical lines to high winds and falling trees. In addition to posing a direct hazard

to anyone caught below the falling lines, derecho damage to overhead electric lines sometimes results in massive,

long-lasting power outages. Hundreds of thousands of people may be affected; in the worst events,

power may not be restored for many days. It is the dense concentration of overhead distribution feeders

in urban areas, and their frequent proximity to large shade trees, that make cities especially vulnerable to

electrical outages following wind storms. Examples of cities in which derechos have resulted in prolonged power

outages that affected large portions of the metropolitan area include Baltimore, Maryland June 29, 1980, Kansas City, Missouri

June 7, 1982, and Memphis, Tennessee

July 22, 2003.

DERECHO

CLIMATOLOGY

Where and

when derechos are most frequent in the United States

Derechos in the United States are most common in the late spring and summer May through

August, with more than 75 occurring between April and August see graph below. As might be expected,

the seasonal variation of derechoes corresponds rather closely with the incidence of thunderstorms.

Derechos in the United States most commonly occur along two axes. One extends along

the Corn Belt from the upper Mississippi Valley southeast into the Ohio Valley, and

the other from the southern Plains northeast into the mid Mississippi Valley figure below.

During the cool season September through April, derechos are relatively infrequent but

are most likely to occur from east Texas into the southeastern states.

Although derechos are extremely rare west of the Great Plains, isolated derechos

have occurred over interior portions of the western United States, especially

during spring and early summer. Additional climatological information on United

States derechos is available here.

Derechos

outside North America

Derechos likely occur in other areas of the world where meteorological conditions are

favorable for their development. However, only one such event has been formally

documented in recent years. On July 10, 2002, a serial derecho occurred over

eastern Germany and adjacent portions

of neighboring European countries. In Berlin and surrounding areas, 8 people were killed

and 39 were injured, mainly from falling trees. In Bangladesh and adjacent

parts of India, a type of storm known as a Nor wester

occasionally occurs in the spring. From various descriptions and knowledge of the meteorological environments involved, it appears that some

of these storms may be progressive derechos.

TORNADOES

IN DERECHO ENVIRONMENTS

and tornadoes can occur with the same convective system. This is particularly so with

serial derechos associated with strong, migratory low pressure

systems. The tornadoes may occur with isolated

supercells rotating thunderstorms ahead of the derecho producing squall

line, or they may develop from storms within the squall line itself. An example of a

serial derecho that produced both extremely damaging straight-line winds and significant

tornadoes from supercells embedded in the derecho-producing squall line is that which

affected Florida during the early stages of the Storm of the Century of March

12-13, 1993. Although not as common, tornadoes sometimes occur with progressive derechos. When they do,

the tornadoes typically form within the bow echo storm system itself, and only rarely are associated with isolated supercells ahead of the bow.

NOTEWORTHY

DERECHOS IN RECENT DECADES

Many significant derechos i.e.,

those that have caused severe damage and/or casualties, have occurred over North America during the

last few decades. Most of these affected the United States and Canada. Listed below is a selection

of some of the more noteworthy events in recent years; the list is not all-inclusive. Information provided in the links includes a map

of the area affected, and a description of the storm s impact.

Holiday weekend events

The human impact of the following events was enhanced by their occurrence on summer holiday

weekends, causing many to be caught out-of-doors during the sudden onset of high winds

July

4, 1969. The Ohio Fireworks Derecho. MI, OH, PA,

WV

July 4, 1977. The

Independence Day Derecho of 1977. ND, MN, WI, MI, OH

July 4-5, 1980 The

More Trees Down Derecho. NE, IA, MO, IL, WI, IN, MI, OH, PA, WV, VA, MD

Sept.

7, 1998. The

Syracuse Derecho of Labor Day 1998. NY, PA, VT, MA, NH

Sept. 7, 1998

The New York City Derecho of Labor Day 1998. MI,

OH, WV, PA, NJ, NY, CT

July 4-5, 1999 The

Boundary Waters-Canadian Derecho. ND, MN, ON, QB, NH, VT, ME

The derechos of mid-July 1995

The mid-July 1995 derechos were noteworthy for both their intensity and range

Series

Overview.Montana to New England

July 12-13, 1995.. The

Right Turn Derecho. MT, ND, MN, WI, MI, ON, OH, PA, WV

July 14-15, 1995.. The

Ontario-Adirondacks Derecho. MI, ON, NY, VT, NH, MA, CT, RI

Serial derechos

Two well-documented, classic events over the eastern United States

April

9, 1991 The West Virginia Derecho of 1991. AR,TN,

MS, AL, KY, IN, OH, WV, VA, MD, PA

March 12-13, 1993. The Storm of the Century

Derecho. FL, Cuba

Southward bursts

Southward burst is a term coined by

Porter et al. in a 1955 paper see reference here to describe a progressive-type squall line that surges

rapidly southward rather than east

May

4-5, 1989 The Texas Derecho of 1989. TX, OK, LA

May 27-28, 2001.. The

People Chaser Derecho. KS, OK, TX

Other noteworthy events

June

7, 1982.. The Kansas City Derecho of 1982. KS,

MO, IL

July 19, 1983.. The

I-94 Derecho. ND, MN, IA, WI, MI, IL, IN

May 17, 1986. The

Texas Boaters Derecho. .TX

July

28-29, 1986.. The Supercell Transition Derecho. IA, MO,

IL

July 7-8, 1991. The

Southern Great Lakes Derecho of 1991. SD, IA, MN, WI, MI, IN, OH, ON,

NY, PA

May 30-31, 1998.. The

Southern Great Lakes Derecho of 1998. MN, IA, WI, MI, ON, NY

June 29, 1998. The

Corn Belt Derecho of 1998. NE, IA, IL, IN, KY

July 22, 2003 The

Mid-South Derecho of 2003. AR, TN, MS, AL, GA, SC

May 8, 2009. The

Super Derecho of May 2009. KS, MO, AR, IL, IN, KY, TN, VA, WV, NC

DERECHOS IN 2004 AND LATER YEARS

The Storm Prediction

Center s severe weather records have been examined to determine those severe

weather events that involve widespread damaging winds associated with convective

storms. Information about these events, which include all the derechos that

have occurred within the United States, has been gathered for the years 2004

and 2005. These records are preliminary and do not include the official National Weather

Service report information listed in Storm Data. They also do not include reports

from Alaska and Hawaii. Information on events that have occurred in more recent years will

be added as time permits. Data has been added on the

Super Derecho that crossed parts of Kansas, Missouri, and Illinois and adjacent states

on May 8, 2009 see link under Other noteworthy events above.

PICTURES AND VIDEOS OF

DERECHOS

A video

has been prepared by the Atmospheric Environment Service of Canada on the progressive derecho that

crossed the Pakwash forest of northwest Ontario on July 18, 1991. This video includes

camcorder footage of the storm affecting a forested area, post storm

aerial views of the forest blowdown,

and interviews with people that experienced the storm.

On

May 27-28, 2001, a Southward burst derecho affected parts of

the southern Great Plains from southwest Kansas into central Texas. Numerous photographs of

the menacing gust front cloud structure associated with the derecho, and videos showing the

damaging winds in progress, were taken on that day. A few images from the event may be seen

by clicking the hyperlink at the beginning of this paragraph.

REFERENCES

Here is a list of selected of scientific

papers about derechos and the convective systems responsible for their development. In addition to presenting analyses of some

well-documented events, these papers describe what is known about the formation and mechanics of derecho-producing convective

systems.

_____________________________________________________________________________

Contact Stephen Corfidi for About Derechos feedback

Acknowledgments

Many people assisted in preparing

About Derechos by providing photos, images, stories,

suggestions, and other information. This assistance was very

much appreciated. From Environment Canada: Phil Chadwick, Rene

Heroux, Mike Leduc, Serge Mainville, Brian Murphy, Peter Rodriquez, Sarah Scriver,

Dave Sills, and Pierre Vaillancourt. From the National Weather Service

and National Severe Storms Laboratory: James Auten, Bert Barnes, John Cannon, Mike Coniglio,

Sarah Corfidi, Chuck Doswell, Roger Edwards, Randy Graham, Jared Guyer, John Hart, Victor Homar, David Imy,

Sarah Jamison, Ed Jessup, Rusty Kapela, Steve Keighton, Richard Koeneman, Norvan Larson, Jeff Last, Jay Liang,

Dan McCarthy, Peter Parke, Steve Pennington, Tom Reaugh, Kevin Scharfenburg, Russ Schneider, Todd Shea, Rich Thompson,

Frank Wachowski, Jeff Waldstreicher, Steve Weiss, and Mike Wyllie. Others who assisted include Curtis Alexander, Marlin

Bree, Dave Crowley, Dave Lewison, Pete Pokrandt, Colin Price, Kristina

Reichenbach, and Robert Schlesinger. Special appreciation is extended to Dennis Cain for use of his excellent

schematic illustrations in Derecho-producing storms, Derecho development, and Derecho climatology.

The BTD-300 Thunderstorm Detector is a standalone sensor that reliably detects the presence of all forms of lightning to a range of 83 km. The unique quasi.

National Weather Service Glossary Here are the results for the letter b B Abbreviation used on long-term climate outlooks issued by CPC to indicate areas that.

Dec 02, 2014 First Person and Third Person S imple, direct storytelling is so common and habitual that we do it without planning in advance. The narrator or teller.